Root Causes: Addressing Oral Health Disparities

Editor’s Note: This story originally appeared in the summer 2023 issue of NEXT magazine. Our online version includes more stories about innovative research happening on the MCV Campus.

Editor’s Note: This story originally appeared in the summer 2023 issue of NEXT magazine. Our online version includes more stories about innovative research happening on the MCV Campus.

By Holly Prestidge

Cheerful, bustling dentists’ offices in rural coastal communities and sleepy mountain towns, all many miles from Richmond. An efficient, high-tech machine in a lab that cranks out crowns and dentures in a matter of minutes and saves patients the emotional and financial angst of making return trips to the dentist.

Water bottles with fluorinated drinking water in the hands of little ones.

Telehealth screentime. Interpretation services.

The list goes on.

The VCU School of Dentistry is attacking oral health disparities from all angles — one tooth, one patient, one community at a time.

Oral health today is widely recognized as vital to overall health. Yet despite gains made in recent decades to align its importance with general medical awareness and understanding, large gaps remain in oral health access and equity for many families and communities around Virginia and the nation.

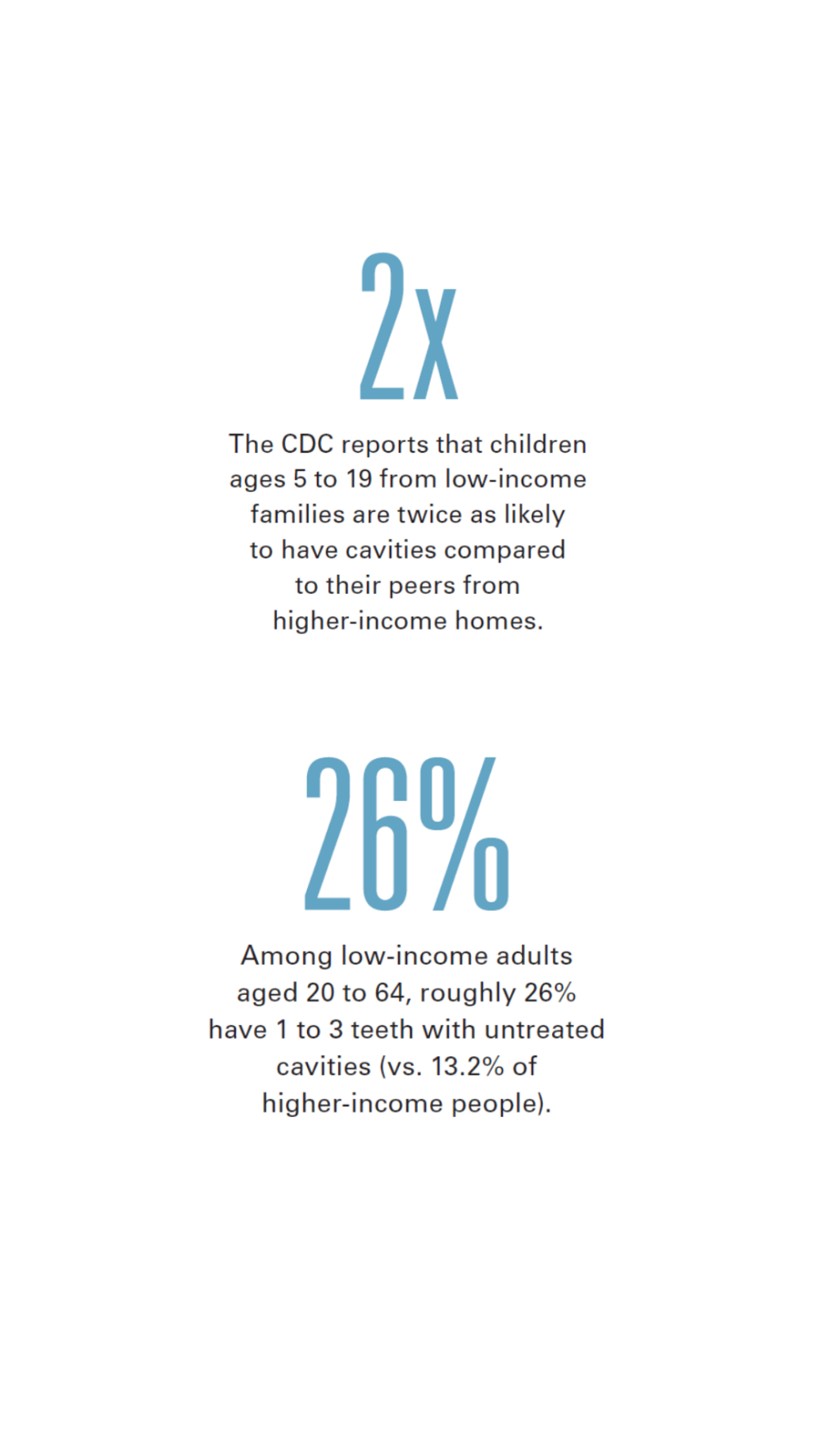

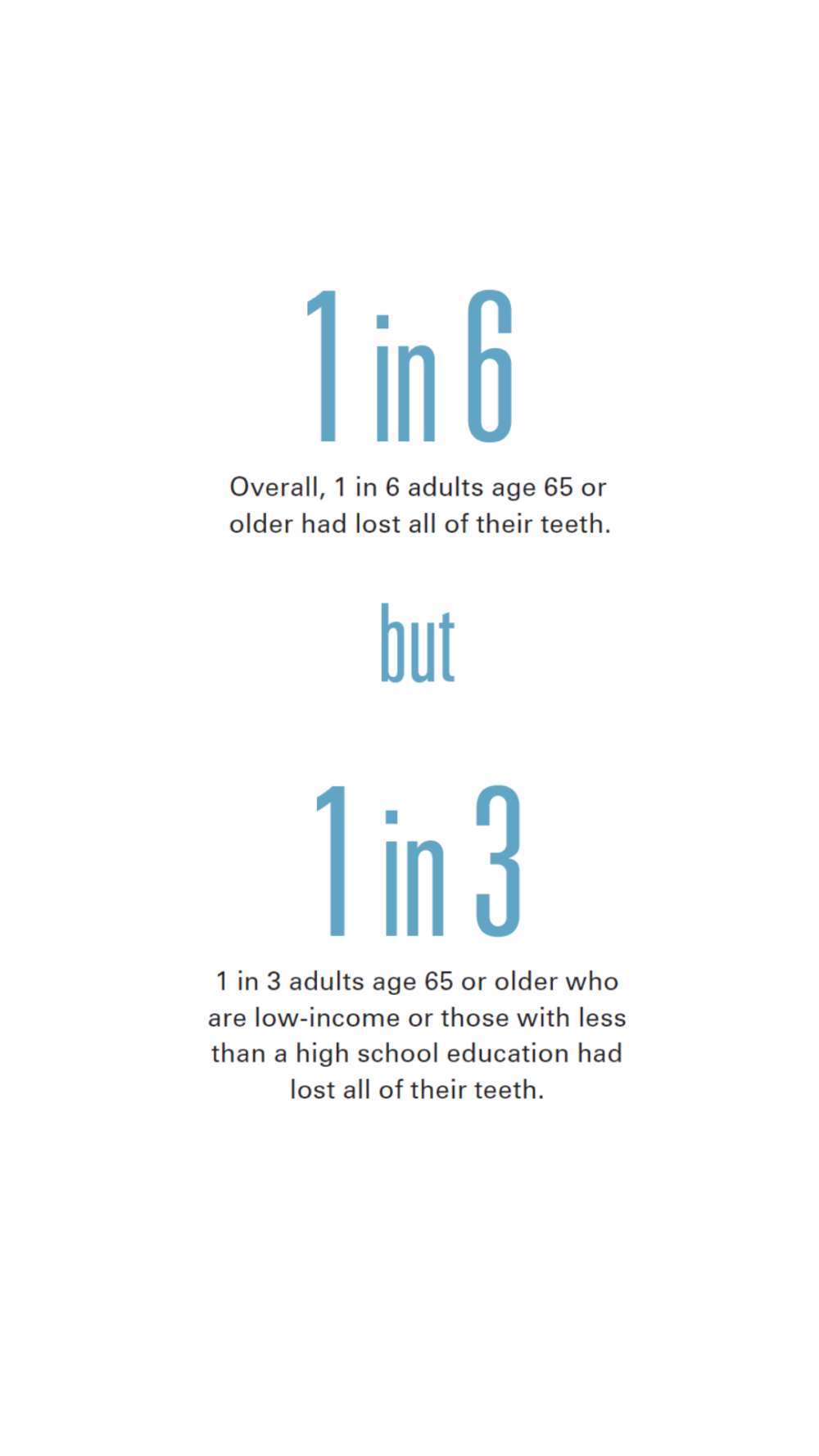

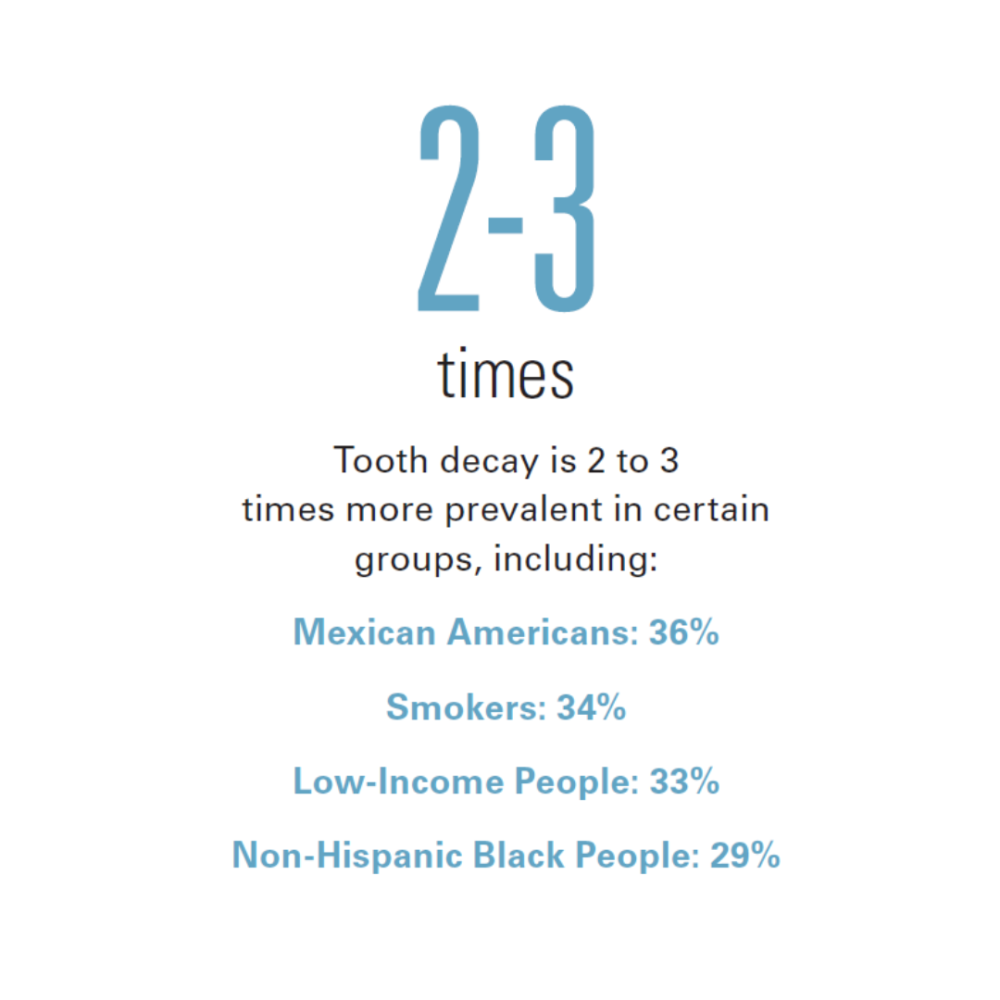

Cavities, severe gum disease and tooth loss — the top three oral health conditions, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention — plague low-income, elderly and other communities two to three times more than other groups. That causes a ripple effect that leads to millions of hours of lost school time for children and upward of $45 billion in lost U.S. productivity for adults.

Tooth pain or losing teeth makes it hard to eat and, sometimes, even hard to speak. Improper nutrition sets off any number of health issues. Oral pain affects social interactions and can derail employment opportunities.

Tooth pain or losing teeth makes it hard to eat and, sometimes, even hard to speak. Improper nutrition sets off any number of health issues. Oral pain affects social interactions and can derail employment opportunities.

As Virginia’s only dental school, VCU sees those disparities and is working to change the oral health landscape across the commonwealth.

Faculty and senior students go to the farthest reaches of the state to see patients who otherwise have no dental care options. Faculty work with local school divisions to implement hydration programs that encourage children to drink water and not sugary beverages, which can lead to cavities but also other problems, such as obesity.

The School of Dentistry is investing in technology. It’s reaching out to patients in new ways to meet them where they are, and the school is structuring its curriculum so that students not only understand oral health disparities but also are equipped to face them.

It’s all about filling in the gaps where people need it most.

Expanding Access

Bill Broas, D.D.S., took a break from seeing patients and shared that he has fitted more dentures in the last two years than he did in nearly 30 years of private practice.

Dr. Broas oversees the dental office within the Northern Neck-Middlesex Free Health Clinic, a busy place off state Route 3 in Kilmarnock. Under one roof are a health clinic, pharmacy and dental practice, the latter of which looks like any other modern dental practice. On most weekdays, its six dentists’ chairs remain occupied as patients rotate in and out.

The clinic’s patients fit the mold of many in rural communities. Most don’t have private insurance and can’t afford to pay costly dental bills out of pocket. Many rely on Medicaid. They work jobs that make it hard to get to the dentist, or they don’t have reliable transportation. They haven’t received regular dental care, so they come to the clinic with severe oral health conditions. Many need to have teeth pulled.

Last year alone, the clinic welcomed nearly 600 new patients for medical and dental care. In one year, its staff fitted more than 100 patients with dentures, some as young as 35 and others as old as 90.

Part of the influx of new patients stems from a July 2021 change in Medicaid policies in Virginia, which included, for the first time, comprehensive dental coverage. The change opened the door for hundreds of thousands of Virginians to get dental care for everything from routine cleanings, X-rays and fillings to dentures, root canals, oral surgeries and more.

Additionally, to address that sizeable new patient cohort and as an incentive to get private dentists to take on more Medicaid patients, the Medicaid reimbursements to dentists increased by 30% last year — the first dental reimbursement increases in nearly two decades. Even with the increase, reimbursements still fall short, with most providers getting about 70% of their costs reimbursed.

In Virginia, about 20% of private dentists accept Medicaid, and of those, roughly 5% actively take Medicaid patients.

It means, simply, that patients using Medicaid rely heavily on places like the Northern Neck-Middlesex Free Health Clinic for low-cost dental care because they can’t get into private dental practices.

The clinic relies heavily on its VCU student cohort, which consists of three dental students and one hygiene student each week for about nine months out of the year. The students each have about 17 appointments per week. The clinic is just one of 14 external rotation sites around Virginia that VCU’s dental students visit throughout their senior year. Dental hygiene students rotate through nine of those.

“Without the students, it would choke us,” said Jean Nelson, the clinic’s CEO and a tireless advocate for both the clinic itself and the community it serves. She recalled that when COVID-19 forced the clinic to close in early 2020, by the time it opened back up later that year, it had 750 missed dental appointments on the books that its staff had to begin addressing. The students have been crucial to meeting this demand.

Dr. Broas, who came out of early retirement to oversee the dental clinic, echoed those thoughts.

“It’s unbelievable how committed they are,” he said about the students. “They put their nose to the grindstone here, and they work — they don’t shy away.”

Not only do VCU dental students provide necessary care, but they also are exposed to populations that epitomize the faces of oral health disparities. In some cases, that exposure opens their eyes to the importance of public health.

Marim Hanna, a VCU dental student working in the clinic, said traveling to external sites like the clinic is rewarding.

“The patients are happy and so appreciative,” she said. “In places like Kilmarnock, there are no other dentists that accept Medicaid, and we provide good, high-quality services.”

VCU Researcher CONTRIBUTES TO National Report

A 2022 National Institutes of Health report on oral health disparities underscored and expanded on Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General, which was last released in 2000.

A 2022 National Institutes of Health report on oral health disparities underscored and expanded on Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General, which was last released in 2000.

Tegwyn Brickhouse, D.D.S., Ph.D., a professor in the School of Dentistry and an authority on oral health disparities within vulnerable communities, contributed to the 2022 report.

While both reports point out the significance of oral health problems, Dr. Brickhouse said, the newest iteration pushes the need to address those disparities, not just by individual dentists and patients, but systemically, through community programs, hospital systems and schools, as well as state and federal policies.

A Richmond-area pediatric dentist, Dr. Brickhouse leads by example. She helped start a hydration program in Richmond Public Schools that encourages students to drink water. Oral health as a measure of overall health means addressing equity, even for something many take for granted, like clean, drinkable water.

In many vulnerable communities, “People don’t trust their water,” Dr. Brickhouse said. Maybe they don’t trust the pipes where they live, or they’ve seen national incidents of other low-income people suffering from unhealthy pollutants in their water supply.

Bottled water is expensive, and it’s not fluoridated — a key component for healthy teeth.

Dr. Brickhouse also works in local schools to provide telehealth dentistry services where she can.

Addressing disparities starts with providers, health systems and others focusing on each family’s and each patient’s needs. But challenges remain, including a significant disconnect between the providers’ assumptions about why patients were not accessing dental care and the reasons offered by the patients themselves.

“Providers tend to think that people in these communities aren’t prioritizing their oral health, especially those within the Medicaid or low-income populations,” she said, explaining that some providers equate a lack of dental literacy with devaluing oral health.

“Providers tend to think that people in these communities aren’t prioritizing their oral health, especially those within the Medicaid or low-income populations,” she said, explaining that some providers equate a lack of dental literacy with devaluing oral health.

“That’s actually quite the opposite,” Dr. Brickhouse said, explaining that the inadequacies of the oral health care system are barriers to care that are mainly out of patients’ control. Barriers include the cost of dental care and coverage, lack of availability of appointments, culture, language and health literacy, and awareness of care options.

“Most people who work hourly jobs can’t come to appointments between 8 a.m. and 5 p.m., and they can’t miss a whole day of work for a two-hour appointment,” she said. “The systems and the way the care is delivered means it’s very hard for people to access.”

Those issues are further complicated if the patients don’t have transportation or they have language barriers and no access to translators or interpretation services.

“The system is not really in line with what these communities need,” she said, explaining that above all, patients reported delaying dental care due to feeling embarrassed about their oral health and not welcomed or respected in the dental office.

“They may have delayed their care for so long that now it appears they haven’t taken care of themselves,” she said. “But they do value it, and they do know it’s important — they just aren’t able to balance that with all the other issues and barriers.”

In the fall of 2020, the School of Dentistry added to the curriculum a mandatory course on diversity, equity and inclusion that ensures students understand the history and are trained to examine biases in health care. Since then, the school has implemented a dental public health course that dives into social determinants of health and health equity by looking through the lens of COVID-19 and the growth of teledentistry and medical-dental integration.

Looking to the Future

Inside the school’s digital dentistry lab on the MCV Campus, Brandy Greer pointed to a large machine and remarked frankly, “That’s a workhorse.”

Greer, assistant manager for digital dentistry and a dental assistant, was referring to a digital mill that routinely cranks out crowns and dentures of various materials. The machine itself looks ordinary, and while patients will never see it, its presence at VCU is a game-changer in closing the gap in oral health disparities.

The School of Dentistry facilitates about 100,000 appointments annually for more than 32,000 patients. Of those, 42% are covered by Medicaid.

In short, having in-house services speeds up the workflow and eliminates the need for outside resources. Patients benefit in lots of ways.

“We have a lot of patients who have to get rides or take the bus to get here,” she said. “Having services in-house means that if they need adjustments during their visit, we can refabricate something right here and have them stay, so they don’t have to make another appointment.”

Some crowns, for example, can be milled in less than a half hour, then stained and glazed and fired in ovens — all in about an hour. The fees normally associated with sending lab work away are cut, and those savings are passed along to patients.

“They don’t have to miss a full day of work or worry about someone watching their kids all day,” Greer said. “It cuts back on missed work time, child care, finding rides or taking the bus, and it’s very affordable.”

The lab also has various printers that create implant placement surgical guides for students as well as orthodontist materials — services that used to be done off-site.

She added: “We’re helping in pretty much every way we can.”

The School of Dentistry’s commitment to health equity and access marches forward. Earlier this spring, Carlos S. Smith, D.D.S., was named inaugural associate dean for inclusion excellence, ethics and community engagement. Dr. Smith joined the faculty in 2015 and has served in several roles that underscore and facilitate the school’s mission to provide high-quality care to all.

The School of Dentistry’s commitment to health equity and access marches forward. Earlier this spring, Carlos S. Smith, D.D.S., was named inaugural associate dean for inclusion excellence, ethics and community engagement. Dr. Smith joined the faculty in 2015 and has served in several roles that underscore and facilitate the school’s mission to provide high-quality care to all.

Since 2020, he’s been an associate professor in the Department of Dental Public Health and Policy and served as the school’s first director of diversity, equity and inclusion. He also directed its ethics curriculum.

Dr. Smith’s new role involves leading comprehensive and integrated strategies to ensure inclusive excellence for all stakeholders, from patients and students to faculty and staff. He’ll expand on community engagement opportunities that are critical to improving access to care.

“This role aligns closely with the priorities outlined in our new five-year strategic plan, impacting not only our efforts to create an inclusive and welcoming environment for our students, faculty and staff, but also focusing resources on improving the experiences of our patients daily,” said Lyndon Cooper, D.D.S., dean of the School of Dentistry.

Dr. Smith said he’s particularly excited to grow the school’s DEI infrastructure and team, and to align the ethics curriculum with the school’s organizational values in ways that mitigate barriers to access for many people.

“Ensuring an understanding of our ethical commitments to health equity and access to care is key for me,” Dr. Smith said. “I am elated to take on this new role to champion our community engagement efforts with collaborative partnerships and patient demographic groups, both across the commonwealth and specifically in the Richmond area.”

If you would like to support the VCU School of Dentistry, please contact Gloria Callihan, the school’s associate dean for development, at 804-828-8101 or gfcallihan@vcu.edu.

Healthier for All

View more stories from our ongoing series about health equity.