Fighting Fentanyl

Editor’s Note: This story originally appeared in the winter 2023 issue of NEXT magazine. Our online version includes more stories about innovative research happening on the MCV Campus.

By Holly Prestidge

An individual arrives at a busy hospital emergency room experiencing a drug overdose. Their skin is cold and clammy. If they’re even conscious, they’re shaking uncontrollably and have trouble breathing. They’re confused and can’t focus on what’s happening to them.

Fast-acting doctors and nurses suspect opioids, possibly fentanyl, and administer naloxone, a common opioid antagonist used in the emergency treatment of overdoses.

Naloxone is effective, but it’s a short-acting agent and wears off quickly, sometimes in less than an hour. Fentanyl, on the other hand, a powerful synthetic opioid, can linger in the body for much longer. Additional doses of naloxone are sometimes necessary to continue to fight off the residual waves of respiratory depression caused by fentanyl, but administration and timing are crucial.

Naloxone, while lifesaving, can also produce acute opioid withdrawal symptoms that sometimes lead people who’ve overdosed before to take their chances and refuse further treatment rather than dealing with its side effects.

If the patient seems stable and leaves the hospital, or the naloxone dosage wasn’t enough the first time — or the hospital runs out of the drug — there’s a chance the patient may die.

VCU Health researchers and scientists are charging ahead to find the answer to a decades-old opioid crisis that, in Virginia, now claims more lives than automobile accidents and guns combined.

Their efforts are critical.

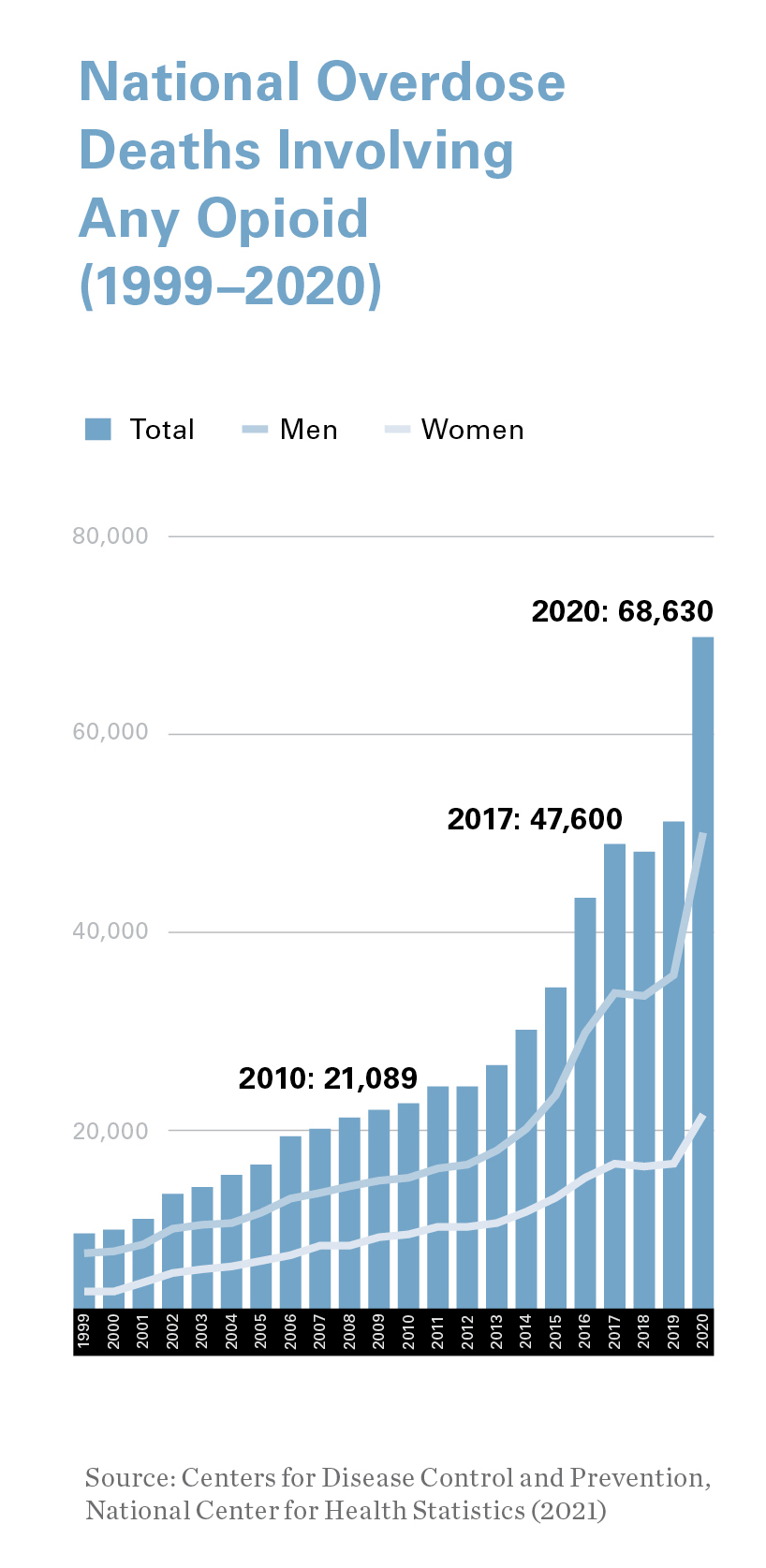

A recent Washington Post report, citing 2021 data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, revealed that fentanyl kills more adults ages 18 to 49 nationally than car accidents, suicides, guns or falls.

The dramatic rise in synthetic opioid-related deaths that started during COVID-19 spurred several actions by the federal government, including a $1.5 billion aid package announced last fall that provides, among other things, increasing access to overdose medicines like naloxone for first responders.

That was followed by the announcement in late 2022 of a new website that would be updated every two weeks with nonfatal opioid overdose data, collected at the county level in all 50 states from EMS first responders. Joining that fight is Yan Zhang, Ph.D., professor of medicinal chemistry at the VCU School of Pharmacy and member of the VCU Institute for Drug and Alcohol Studies. In July 2022, he was awarded a $2.8 million grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse to advance his research into the development of specific opioid receptor antagonists that would reverse the acute and chronic toxicity of fentanyl.

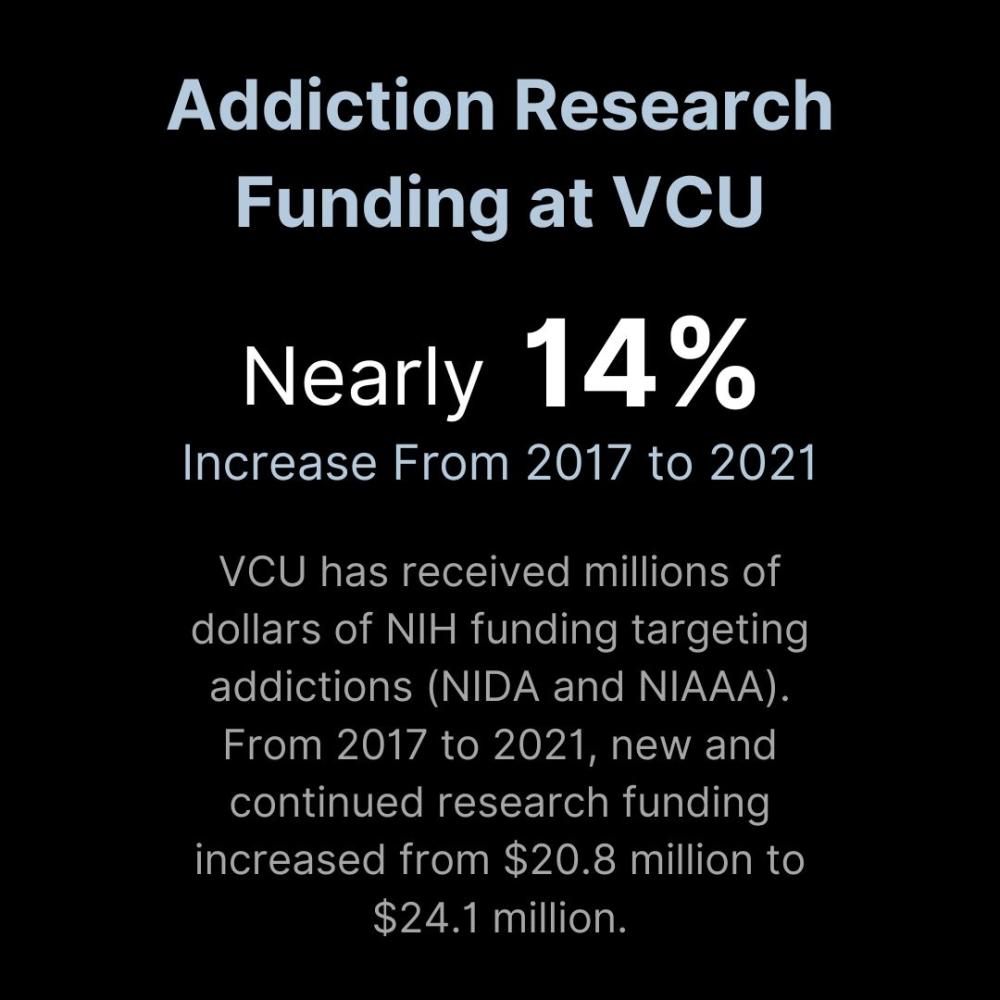

His grant underscores VCU’s status as a leading research institution for opioid use disorder. Last year, VCU was awarded $16.5 million in NIDA funding, placing it 18th nationally.

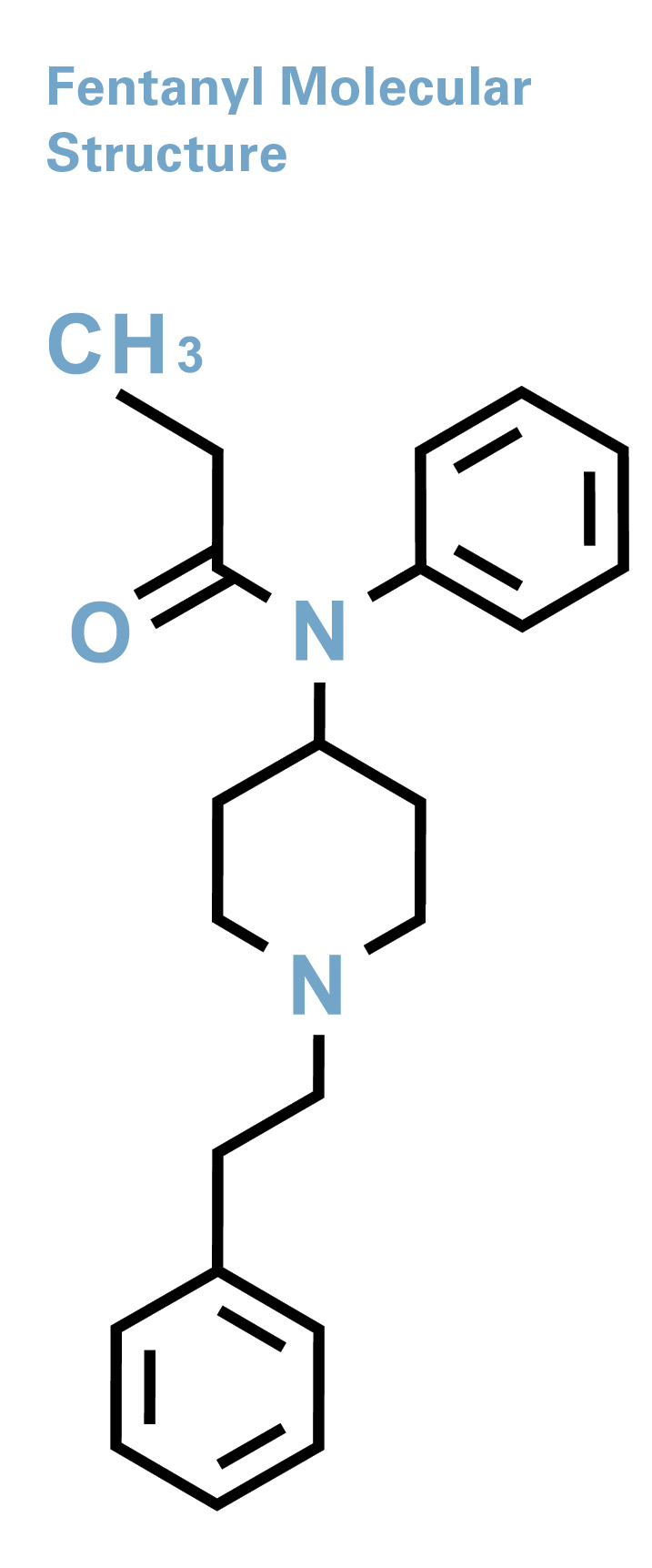

While he has dozens of research grants to his name, this one is Dr. Zhang’s second grant in recent years pertaining to opioid use disorder. He received an NIH/NIDA grant in 2019, worth just over $2 million, for development of novel mu opioid receptor modulators, with the goal of conducting preclinical studies on several novel lead compounds for opioid use disorder treatment. Mu receptors are among a family of critical proteins in the body that modulate pain, but major side effects from the application of common mu opioid receptor agonists — such as morphine and fentanyl — are abuse and addiction, and even overdose.

“We want to develop a more effective treatment for fentanyl overdoses that tackles the interaction between fentanyl and mu opioid receptors,” Dr. Zhang said of his most recent grant.

Potent Problem

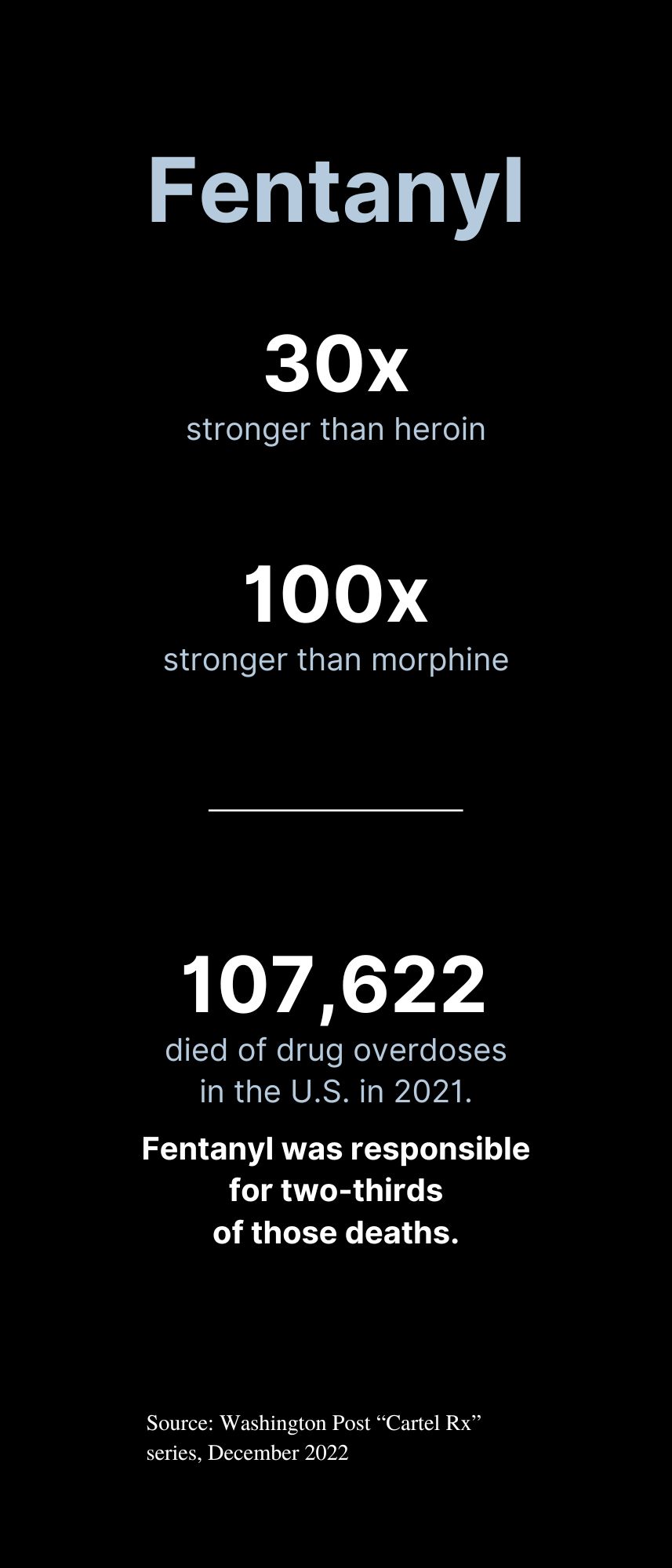

Fentanyl packs a dangerous punch. It’s 100 times more potent than morphine and at least 30 times more potent than heroin.

Fentanyl packs a dangerous punch. It’s 100 times more potent than morphine and at least 30 times more potent than heroin.

It’s often reserved to treat the most severe cases of acute and chronic pain. Like other opioids, fentanyl targets mainly mu opioid receptors, which are found on cells throughout the body. When opioids attach themselves to these receptors, they block the body’s pain receptors in the brain, stimulating its pain management mechanisms. They also send waves of dopamine into the brain, creating feelings of euphoria — the sort of high that leads patients to addiction.

Medical supervision is imperative, as a few milligrams of fentanyl are enough to kill an adult. Research shows that as little as one week’s worth of fentanyl can lead to addiction, especially for those who may be genetically predisposed to it.

Yet for many who use opioids outside of a doctor’s watchful eye, access is as easy as ordering the drugs by mail, and use can lead to a variety of side effects including death.

Opioid misuse can produce a variety of gastrointestinal issues such as nausea and vomiting, along with fatigue. But the most serious side effect is respiratory depression — shallow breathing and an irregular or slow heartbeat — which can lead to death, said Dr. Zhang.

He described the opioid crisis as needing a three-pronged solution. In layman’s terms, he said, that’s improving lives, changing lives and saving lives.

Part of the challenge is tackling not only fentanyl’s toxicity, but also polysubstance abuse addiction, where fentanyl is mixed with other opioids.

Improving lives means finding effective, nonaddictive pain management medications that minimize the risk of addiction when individuals are first introduced to opioids, usually as patients in the hospital.

The grants he’s secured, however, support research for the other two stages — changing and saving lives. He explained that changing lives means developing effective medications for those who are already addicted but working through therapy. His 2019 grant supported this research.

His current research focuses on the direst stage of the crisis — the overdose. He’s working to develop a chemical counteragent that will block fentanyl’s ability to attach itself to the mu opioid receptors. Part of the challenge is tackling not only fentanyl’s toxicity, but also polysubstance abuse addiction, where fentanyl is mixed with other opioids.

Overdose deaths involving fentanyl often occur not from fentanyl alone — it’s often added to other street drugs, unbeknownst to users.

“When they are mixed together, the scenarios can be very difficult to tackle as researchers,” Dr. Zhang said. “If you make something that responds to fentanyl, it will also have to respond to other substances that the fentanyl is mixed with.”

Zhang is working with an expert team at VCU and VCU Health of chemists, biologists and pharmacologists. Within that team is psychiatrist and addiction expert F. Gerard “Gerry” Moeller, M.D., director of VCU’s Wright Center for Clinical and Translational Research and the university’s associate vice president for clinical research. Dr. Moeller also leads the VCU Institute for Drug and Alcohol Studies.

Dr. Moeller echoed Dr. Zhang, in that increasingly today, overdoses often have a common element: the presence of fentanyl.

“Fentanyl is really potent so if you’re not tolerant to opioids, it’s very easy to overdose,” Dr. Moeller said. “Fentanyl can be put into other things in really small amounts and have a big effect.

“We’re seeing overdose deaths with cocaine, for example, but it’s not from the cocaine itself,” he added. “It’s the fentanyl being added to the cocaine.”

Naloxone is the go-to medication for overdoses, but it has its limitations, Dr. Zhang said.

Naloxone is the go-to medication for overdoses, but it has its limitations, Dr. Zhang said.

“Your body metabolizes very quickly so the naloxone will disappear, but the fentanyl lives on in your body, maybe for several hours,” Dr. Zhang said, “which means you have to be given multiple doses of naloxone.”

The danger doesn’t go away once an individual survives an overdose. In fact, it’s the opposite. After one overdose, “the odds of you having a repeat overdose and dying are really high,” Dr. Moeller said.

Leading the Way

In April 2017, VCU Health opened the Multidisciplinary Outpatient Intensive Addiction Treatment Clinic, or the MOTIVATE Clinic, as it’s called, in Richmond’s Jackson Ward community. The facility helps those who are struggling with addiction, many of them referred to the clinic from nearby VCU Medical Center after an overdose.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in 2021, more than 80,000 people died from opioid overdoses nationally, a statistic fueled, in part, by a worldwide pandemic.

“The stress of COVID, including the loss of employment and other factors, led to an increase in substance abuse, which led to increases in opioid use and overdoses,” Dr. Moeller said.

Compounding the problem was a lack of access to treatment, as clinics and treatment facilities initially shuttered their doors at the onset of the pandemic. But by the time COVID-19 struck in early 2020, VCU was nearly three years into a groundbreaking program that was already changing the local landscape in the treatment of opioid use disorder for both patients and medical personnel.

The MOTIVATE Clinic’s novelty lies in its approach: Rather than patients leaving hospitals and being referred to outside agencies for treatment, where they can sometimes get lost or lose interest when left to initiate treatment on their own, MOTIVATE links emergency services directly to a treatment facility.

That straight line within the same health system has proved effective and is further enhanced by thoughtful programs that approach treatment from two different areas: medication, with patients treated with buprenorphine, which reduces cravings for opioids, but also behavioral and counseling services.

By June 2017, a few months after opening, the clinic had reached upward of 80 people. Today, Dr. Moeller said, the clinic treats more than 400 people every month.

One key component that has contributed to the clinic’s success is the ever-expanding group of health care professionals who understand that opioid use disorder affects everyone — from teens to pregnant women to seniors — and have incorporated addiction medicine into their roles. Within the MOTIVATE Clinic are social workers, physicians and nurses, but also general or family practitioners, OB/GYNs, internal medicine doctors and emergency medicine physicians.

What’s Next?

VCU Health didn’t stop with the MOTIVATE Clinic. One of the few changes resulting from COVID-19 was a relaxing of federal regulatory policies regarding telehealth services, including allowing doctors to prescribe medications for opioid use disorder.

VCU Health didn’t stop with the MOTIVATE Clinic. One of the few changes resulting from COVID-19 was a relaxing of federal regulatory policies regarding telehealth services, including allowing doctors to prescribe medications for opioid use disorder.

Under Dr. Moeller’s leadership, and with funding from a federal grant administered by the Virginia Department of Medical Assistance Services, the VCU Health Virtual Bridge Clinic was created in April 2021.

As its name implies, the virtual program is the invisible bridge between the emergency room and the MOTIVATE Clinic, so patients have a clear course of treatment available to them before they even leave the hospital.

Timing is everything.

“For patients with opioid use disorder, stress and depression and other factors means their motivation to engage in treatment fluctuates over time,” Dr. Moeller said. “So, if they’re ready to seek treatment while they’re in the emergency room, you need to be able to get them into treatment right away as opposed to giving them information and telling them to call, then wait on treatment that might be three or four weeks down the road. By that point, they may have had an overdose.”

Dr. Moeller said all these elements — from research capabilities and in-house programming to involvement in statewide initiatives — have positioned VCU as a global leader in combating addiction and specifically, opioid use disorder.

With VCU Health Virtual Bridge Clinic, providers can get patients an appointment within 24 hours and to get them started on medication via telehealth.

“They don’t have to come in, they can be at home, they don’t have to find transportation,” Dr. Moeller said. “Then, we prescribe the medication and bridge them all the way until they get into a face-to-face appointment. We’ve seen a lot of success with that.”

Dr. Moeller said the clinic has also received interest from the Virginia Department of Corrections, which is looking to bolster treatment programs for inmates with opioid use disorder.

Dr. Moeller said the clinic has also received interest from the Virginia Department of Corrections, which is looking to bolster treatment programs for inmates with opioid use disorder.

“Of the people who made it into our bridge, almost 75% of them made it across,” he said, a significant step forward when compared with a system that requires patients to seek treatment on their own.

Going one step further, VCU is also working with Virginia’s Emergency Department Care Coordination Program, a statewide system that connects emergency rooms around the state by sharing information in real time about patients who receive emergency services.

“To my knowledge, there are very few places in the country or maybe the world that have the level of interaction and programs going on to target addictions and opioid use disorder,” he said. “It ranges from the science that Dr. Zhang is doing, creating chemicals in the lab, to getting FDA approval for medications, to getting them to patients through telehealth and working with emergency rooms and other agencies.”

Dr. Moeller said all these elements — from research capabilities and in-house programming to involvement in statewide initiatives — have positioned VCU as a global leader in combating addiction and specifically, opioid use disorder.

“There’s been a great shift in the history of the overuse of prescription opioids and that’s very positive,” Dr. Moeller said. “At VCU, we’re in the next phase, which is how do we treat the significant number of individuals who have opioid use disorder and keep them from becoming a statistic.”

If you would like to support addiction research at VCU, please contact Heather Phibbs, director of development for the neurosciences in the Office of Medical Philanthropy and Alumni Relations, at 804-628-8907 or heather.phibbs@vcuhealth.org.

Make an Impact

Support addiction research at VCU Health