Predicting Dementia

Editor’s Note: This feature was originally published in the summer 2025 print edition of NEXT. To view a PDF of the full issue, visit our publications page.

By Holly Prestidge, MCV Foundation

Maurice Henderson stood in front of dozens of his fellow senior congregants at Fifth Baptist Church in Richmond in early 2025 and introduced a topic that stirs all sorts of emotions for older people: dementia.

Flanking him on both sides were members of various VCU Health and VCU Health Sciences teams who are working to figure out if changes in physical abilities are an indicator of dementia’s onset. They were also there to support Henderson, who does not have dementia but has decided that while he’s healthy, he’s going to do all he can for those who are not.

Henderson is one of 150 people participating in a VCU School of Nursing study that aims to identify physical markers of cognitive decline. These markers can be shared with providers who can intervene early in the disease’s progression and potentially delay the onset of dementia and other cognitive diseases. The five-year, $3.1 million study, funded by the National Institutes of Health, began in 2022 and particularly targets medically vulnerable and underserved communities.

Changes in one’s physical abilities over time, especially changes within daily functions, could indicate a risk of dementia. The study looks at the physical abilities of people ages 65 and older who do not have dementia. By establishing a baseline of physical markers within healthy individuals, researchers can intervene earlier when they detect changes and offer lifestyle modifications to ward off those risks.

The study, called Life-Space and Activity Digital Markers for Detection of Cognitive Decline in Community-Dwelling Older Adults, works like this: Participants visit VCU about every six months over three years, and during those visits, they complete a series of brain games. The games test memory and recall through exercises involving numbers and words. Participants also fill out surveys, which dive deeply into their lives, revealing everything from how many times they leave their bedroom, their home or their town, to the number of people within their social circles.

We wanted to look at how people moved within their home and their spaces and how all of that could potentially change if they’re developing these cognitive declines, and then look at ways we may be able to intervene early to improve people’s physical functions.

Lana Sargent, Ph.D., associate dean for practice and community engagement, VCU School of Nursing

Before they leave those visits, participants are outfitted with a wearable device like a fitness tracker that is worn for a week. They also carry a GPS locator. Over a week’s time, the devices record individuals’ activity levels, while GPS shows their physical locations.

Henderson, a retired engineer whose career has taken him and his family all over the world, knows his community well. He knows they need the facts about dementia and Alzheimer’s now, because the likelihood of experiencing it themselves — or knowing someone with it — is high and increasing every year.

He knows it runs in his family.

Henderson also knows that VCU needs healthy people like him to participate. It’s why he stood before his church friends and neighbors earlier this year and encouraged them to join him. Because for too many, he knows, it is already too late.

A Growing Problem

Dementia is an umbrella term for symptoms related to brain disease that result in impairments in cognitive function and particularly affect one’s daily life. While many think dementia is a normal part of aging, it’s not.

Nearly 10% of adults ages 65 or older in the U.S. have dementia. Another 22% have some degree of mild cognitive impairment. The estimated number of people who have Alzheimer’s disease — the most widely recognized type of dementia — is about 7 million, and that number is expected to nearly double by 2050.

Dementia isn’t just memory loss. The disease manifests in other ways, including loss of communication and language, the inability to focus and pay attention, trouble with visual perception and lack of reasoning and judgment, as well as functional abilities of daily life.

In addition to Alzheimer’s, which collectively kills more people across the U.S. than breast and prostate cancer combined, there are several other types of dementia, including frontotemporal, Lewy body and vascular dementia.

Co-leading VCU’s study are Lana Sargent, Ph.D., associate dean for practice and community engagement at the School of Nursing, and Jane Chung, Ph.D., a former VCU associate professor who remains involved. The study also involves the VCU Mobile Health and Wellness Program and VCU’s Convergence Lab: Health and Wellness Across the Lifespan. They are also partnered with the Osher Lifelong Learning Institute at the University of Richmond.

Dr. Sargent said one of the ways this study differs from others is that it tracks people within their daily lives versus participants who come to VCU to be observed in a clinical setting, which is not where people spend the majority of their time.

“We wanted to look at how people moved within their home and their spaces and how all of that could potentially change if they’re developing these cognitive declines,” she said, “and then look at ways we may be able to intervene early to improve people’s physical functions.”

While the data looks at physical movement, Dr. Sargent said those markers can point to larger issues within the participant’s environment, social circles and overall health, and ultimately, reveal their risk of dementia. For example, if someone does not feel safe leaving the house, the ability to interact with other people lessens, which can lead to loneliness and depression — important factors that have been proved to impact cognitive function.

People know the importance of physical activity, but they don’t know the connection between mobility and the prevention of dementia.

Jane Chung, Ph.D.

The devices capture an individual’s movements, including the amount of time the person is physically active and the intensity of their movements. GPS tracks the geographic area covered while the person is mobile. In all, researchers are hoping to identify as many as 20 indicators from physical activity that they can use to detect cognitive changes.

Dr. Chung, the study’s co-leader, explained that traditional methods of dementia diagnosis include blood biomarkers and imaging biomarkers from MRI or PET scans, which are often expensive and therefore out of reach for many people. By contrast, this study provides data through research using equipment that’s more accessible and affordable to more people.

VCU specifically chose the wearable devices, called Real-Life Activity and Life-Space Mobility Monitoring Solution, or RAMS, for their convenience. Unlike many fitness trackers today that require users to have smartphones and then download apps to get their personal health data, RAMS devices gather data on their own without the use of complicated and often costly technology.

“Translating mobility science into brain health is going to be really important for preventing dementia because there’s a gap in that understanding,” Dr. Chung said. “People know the importance of physical activity, but they don’t know the connection between mobility and the prevention of dementia.”

Data from this study can open conversations between clinicians and patients about lifestyle modifications much earlier in patients’ lives.

In all, over the five-year study, participants will have roughly seven visits at VCU. Dr. Sargent said they continue to recruit study participants, with the goal of enrolling at least another 150 people.

They’re looking for people 65 and older, in relatively good health, who do not currently take prescriptions for dementia.

An Easy Lift

Henderson, 72, chuckled as he shared that he learned about the VCU study when he saw a magazine story about it last year in his doctor’s office. It piqued his interest.

The chuckle is because he took the magazine. (Not just for the study information; his daughter Leah, an author, had a book listed in the magazine’s summer reading list.)

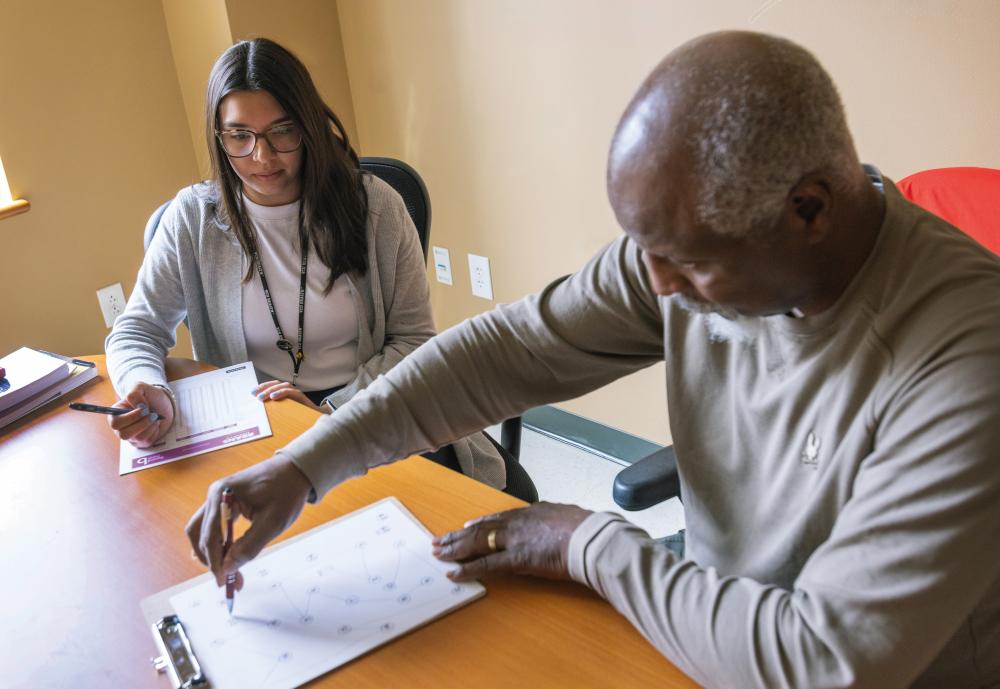

“It’s clear that we all need to know more,” Henderson said earlier this spring. He had just finished his second two-hour stint with Hannah Khan, RN, a research nurse with the School of Nursing. The brain teasers, he noted, were a mental workout. For a week, he would wear the device on his wrist, giving researchers glimpses into his life.

Just two sessions in, he’s already learned a few things.

“I’m maintaining a mental yardstick on my performance,” he said. “The experience has raised my awareness of lifestyle options I can choose for my own health.”

He also understands and appreciates the broad network of support available at VCU for people experiencing cognitive impairments and their caregivers. He hopes others will join him in the study.

“We need a rich and diverse population to achieve the best possible findings from this study,” he said. “We cannot achieve any measure of success if we hide the disease.”

Henderson’s family is his inspiration, but countless others will benefit.

“We seek to give a little helping hand whenever we can,” he said, “and this one is an easy lift.”

If you would like to support dementia-related studies at the VCU School of Nursing, please contact Jess Sorensen, the school’s senior director of development, at 804-615-5877 or jlsorensen@vcu.edu.If you would like to learn more about the RAMS study or be a participant, please contact the RAMS study team at sonramsstudy@vcu.edu.

Health. The Greatest Gift for All

Support incredible research at VCU and help train future health care leaders.