Remote Control: Bringing Robotic Surgery to Living Donors

By Holly Prestidge

Four robotic arms extend like metal tentacles over the operating table inside a darkened operating room at VCU Health’s Main Hospital, moving ever so slightly and seemingly at will.

The arms are fitted with thin removable rods, the tips of which hold tiny medical instruments — graspers, suction aids, needle drivers, even a camera.

Their insertion into a living human body via four small punctures initiates an hours-long removal of part of a healthy liver — the first step in a living donor liver transplant. And all of it is captured, thanks to that tiny camera, in wildly vivid, magnified detail on screens all around the room.

Remarkable in their complexity and dexterity, the robot arms are sleek and sophisticated, and their potential impact on living donor liver transplants at VCU Health — not just the critical care but also future research and education — has yet to be fully realized.

Still, the robots are nothing without a human touch, and the VCU Health surgeons leading this procedure are among the most highly skilled in the world.

VCU Health’s Hume-Lee Transplant Center has reached the apex of clinical care for living donor liver transplants thanks to a relentless drive to treat more liver transplant patients, particularly those who historically have not been ideal candidates for liver transplants.

It is using robotic technology to do that. Since April, eight robotic living donor liver transplants have been performed, making Hume-Lee one of only three centers nationally to perform such procedures and the only such center on the East Coast.

It is using robotic technology to do that. Since April, eight robotic living donor liver transplants have been performed, making Hume-Lee one of only three centers nationally to perform such procedures and the only such center on the East Coast.

“Robotic surgery” means surgeons control the robotic arms and their instruments to perform the partial hepatectomy, or removal of the right side of the liver. They manipulate the arms with incredible precision and accuracy from a console on the other side of the operating room.

Compared to traditional open surgeries, robotic procedures cut recovery time nearly in half, and result in fewer complication risks for patients. At an academic health system, the robot also serves as a powerful teaching tool. Add it all up, and VCU stands to offer liver transplants to a wider range of patients with better outcomes than ever before.

Fully robotic living donor liver transplants are the future. At VCU and Hume-Lee, the future is happening right now.

REINVIGORATING THE LIVING DONOR PROGRAM

The liver is the largest solid organ in the body, and its varied functions, from managing blood clotting and filtering toxins from the blood to helping with digestion, are crucial to good health. Liver disease encompasses a variety of conditions, including hepatitis viruses, autoimmune diseases, cancer and more.

The American Liver Foundation estimates that upward of 100 million people have some degree of liver disease, but many do not know they have it. An estimated 4.5 million people are diagnosed annually. Roughly 10,000 people with the worst cases of end-stage liver disease await liver transplants each year around the U.S.

In 2022, Hume-Lee performed nearly 170 liver transplants and it expects to surpass that number in 2023 with 180. The vast majority will be open surgeries and not robotic, but the goal — 100% robotic living donor liver transplants — is within sight.

It is not a stretch for a health system that has led the transplantation field for decades.

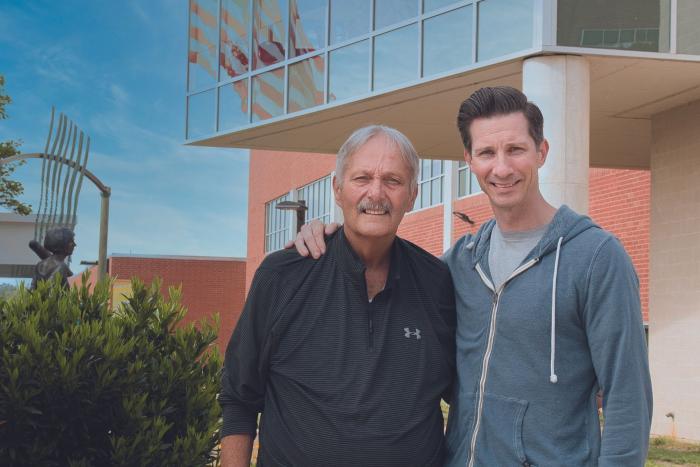

David Bruno, M.D., interim chair of both Hume-Lee and the VCU School of Medicine’s Division of Transplant Surgery, flashed a grin as he recalled stories of VCU’s renowned transplant history.

He was recruited to VCU in 2019 but is quick to sing its praises as an institution with an illustrious, decades-long past, one that largely started with the transplant center’s namesake, David M. Hume, M.D.

Dr. Hume successfully performed the first kidney transplant in 1957, and in the early 1960s, laid the foundation for VCU’s current transplant program. Dr. Hume was later joined by Hyong Mo Lee, M.D., who added liver, pancreas and liver cell transplantation to the center’s capabilities.

Compared to traditional open surgeries, robotic procedures cut recovery time nearly in half, and result in fewer complication risks for patients.

Decades later, in 1984, Dr. Lee, then president of the American Society of Transplant Surgeons, pushed for the signing into federal law of the National Organ Transplant Act. The law effectively outlawed the sale of human organs and established the basis for a national registry for organ matching, allocation and distribution.

The robotic elements of surgery came after human mastery of the field. In 2014, Hume-Lee launched a robotic surgeries system, using the technology to perform transplants for kidneys and other organs. By 2019, VCU Health had hit the gas pedal when it came to liver transplants. Hume-Lee established a minimally invasive surgery division with a goal of specializing in kidney, liver and pancreas transplants using robot-assisted and laparoscopic procedures.

The underlying intent was to jump-start what had become a stagnant living donor liver transplant program. The efforts were led by Marlon F. Levy. M.D., then the chair of the Division of Transplant Surgery and director of Hume-Lee, and now the interim senior vice president for health sciences at VCU and the interim CEO of VCU Health.

In addition to hiring Dr. Bruno, a noted pediatric transplant surgeon, the transplant center hired Vinay Kumaran, M.D., Hume-Lee’s living liver donor surgical director, whose career includes more than 800 living donor transplant surgeries. It also hired Seung Duk Lee, M.D., Hume-Lee’s associate surgical director of liver transplants, who previously served as a living donor liver transplant surgeon in South Korea. There, such transplants are common.

The team got to work. To prepare for a 2023 launch of the newly invigorated living donor program, Dr. Lee and Dr. Kumaran traveled to South Korea in 2022. There, they observed surgeries performed by the world’s preeminent liver transplant pioneer, Gi Hong Choi, M.D., of Yonsei University College of Medicine’s Division of Hepatopancreatobiliary Surgery, who has performed more than 150 robotic surgeries.

Dr. Lee and Dr. Kumaran brought that knowledge back to the MCV Campus, where they successfully performed VCU’s first and second robotic living donor liver transplants in spring of 2023. Their third and fourth surgeries, however, proved challenging. The physical size of one individual was a concern, and the other had prior surgeries. The team once again reached out to Dr. Choi in South Korea.

That summer, Dr. Choi visited Hume-Lee to aid doctors during those two procedures.

“It’s very complicated and very difficult,” Dr. Lee said of robotic liver transplants, noting that surgeons need to be highly skilled in open liver transplants before they can begin to train with a robot. “Our plan was to start very slowly and very safely.”

His team spent months preparing to use the robots, and they started by performing hybrid procedures in which the healthy liver was cut both by robots and through open surgeries. Eventually the team advanced into using primarily robot-assisted procedures whenever possible.

“You’re operating on a perfectly healthy patient, so the expectation is that they’ll do well,” Dr. Bruno said. “The most important thing about how we developed this program is that it’s very measured and the patient safety comes first — there’s zero room for error.”

Robots offer benefits that open surgeries do not. Unlike human hands, which need to be steady, robots are tremor-free. The visualization from the camera allows images within the body to be magnified up to 10 times what the human eye can see.

“The camera can see around corners, and you can see up close and then zoom back out and see a larger perspective,” Dr. Bruno said.

Unlike robotic surgeries, open transplant surgeries require large incisions to allow doctors to reach the liver with enough space to work to retrieve it. These larger incisions take longer to heal. Additionally, with open surgeries, cutting through layers of the main muscles in the abdomen — including accessory muscles for actions like breathing — means patients are put at risk for pneumonia and other infections.

The most important thing about how we developed this program is that it’s very measured and the patient safety comes first — there’s zero room for error.

David Bruno, M.D., interim chair of Hume-Lee and VCU School of Medicine’s Division of Transplant Surgery

But with robots, the four arms enter the body through four small punctures rather than a large incision. When the liver portion needs to be extracted, an incision is made that resembles a pregnancy C-section, just below the waistline. Patients report less pain, and scars below the waistline heal in about four to six weeks versus eight to 10 weeks. The smaller incisions also allow for minimal incision scars.

“The difference in the incision is so remarkable,” Dr. Bruno said. “Less scarring means less injury and risk of infection, which ultimately means less morbidity.”

But the robotic benefits do not end there. For academic surgeons, the new technology is the perfect teaching tool.

“These robots have side-by-side consoles so a student can watch as the doctor works at their console to control the robots,” Dr. Bruno said. “In contrast, when I am teaching a fellow during an open surgery, I am not always sure they’re seeing what I’m seeing. But with the robots, the views are the same — they are seeing the same views that I see during an operation.”

Dr. Bruno said for now, robots are used only on donors. The recipients of a new liver are still treated through open surgeries. But the potential is there to eventually reach completely robotic liver transplants.

“The robot provides for all these things,” he said, “innovation, apex clinical care and an outstanding educational component.”

THE FUTURE OF SURGERY

Back in the operating room, Dr. Lee turns away from the console for a moment, stretching his arms over his head.

In all, he spends more than five hours peering into that console, which offers him a 360-degree view of the liver and the surrounding organs. With his hands, he deftly maneuvers joysticks while pushing pedals with his feet — each tap of his foot or turn of his wrist or push of a finger sends commands to the four robotic arms and tiny instruments.

Next to him, at a second identical console, is Dr. Kumaran, who watches from the same vantage point as his trusted colleague. They are not alone. For hours, physicians stand by the operating table as Dr. Lee sits at the console. The attending surgeons remove and reinsert the rods with the medical instruments as needed, sometimes every minute or so, per Dr. Lee’s orders.

Not far away in another operating room, physicians and hospital staff prepare the transplant recipient to receive their new liver.

To support the VCU Health Hume-Lee Transplant Center, please contact Andrew Hartley, director of development in the Office of Medical Philanthropy and Alumni Relations, at 804-305-3055 or aphartley@vcu.edu.

Discover More

Read more features like this in the winter issue of NEXT magazine.