A Suture-less Future for Nerve Repair

By Zaynah Qutubuddin

One of America’s favorite fruits is the culprit for sending more people to the emergency room than one might expect: the avocado.

Avocado hand, as it is aptly named, happens when a person holds an avocado to slice it and accidentally cuts through to the palm. In many cases, individuals end up cutting into nerves and other structures. Nerve injuries in general can result in degrees of disability ranging from isolated numbness in a single finger to devastating loss of function. In many situations, one might even lose all sensation in the fingers and thereby the ability to detect the temperature of a pot or use a smartphone.

Avocado hand, as it is aptly named, happens when a person holds an avocado to slice it and accidentally cuts through to the palm. In many cases, individuals end up cutting into nerves and other structures. Nerve injuries in general can result in degrees of disability ranging from isolated numbness in a single finger to devastating loss of function. In many situations, one might even lose all sensation in the fingers and thereby the ability to detect the temperature of a pot or use a smartphone.

Nerve damage can affect complicated environments throughout the body depending on the site of injury. But as one example, nerves in the hand are particularly difficult to repair. Three major nerves are woven through more than 30 muscles, 27 bones, and various tendons, ligaments and blood vessels. Each finger alone is supplied by four bundles of nerves and blood vessels.

An injury like avocado hand involves peripheral nerve damage, which can affect any nerves in the body that branch out from the brain and spinal cord. Repairing the damage requires the right combination of microsurgical skill and precise alignment of the cut nerve ends. Both are difficult to achieve, and good recovery following major peripheral nerve repair is just 50%. One VCU researcher is working to change that.

People have talked about it before, but nobody has ever made something similar to the prototypes we have.

Jonathan Isaacs, M.D., VCU School of Medicine professor and chair of the Division of Hand Surgery, VCU Health Medical Center

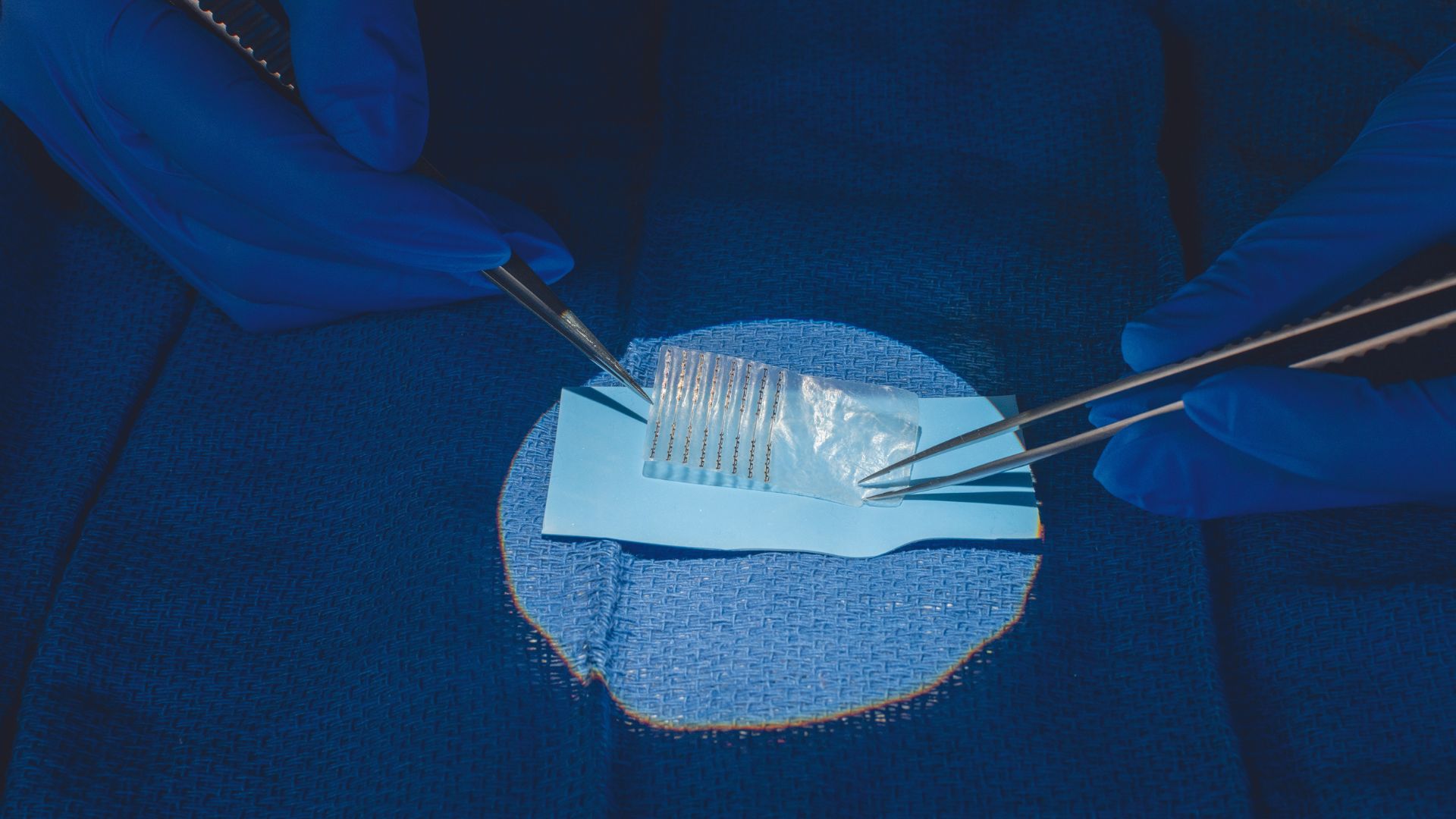

Jonathan Isaacs, M.D., a VCU School of Medicine professor and chair of the Division of Hand Surgery, set out 10 years ago to improve outcomes for nerve repair. His research has led to the invention of Nerve Tape, a patented device with microscopic hooks that creates a tube around nerve ends. The device allows for more precise alignment of nerve ends and mechanical repair strength equal or greater to clinical microsuture repairs. The result is an improved recovery for peripheral nerve injuries over the current standard of care.

“Microsutures are the conventional gold standard way to fix nerves, so we knew Nerve Tape had to be at least as good as that,” Dr. Isaacs said. “And now, after all our testing and research, we know that Nerve Tape is a lot better.”

The invention has received clearance from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, meaning that its development partner, Atlanta-based BioCircuit Technologies, can market the product in anticipation of the first human use in the coming months.

“The development and clearance of Nerve Tape represent a significant advancement in the treatment of nerve injuries,” Dr. Isaacs said. “This product has the potential to offer surgeons a faster, simpler method for achieving a precise, reliable repair of injured nerves.”

RETHINKING THE GOLD STANDARD

Peripheral nerve injuries make up many of the more than 2 million upper extremity injuries reported in the U.S. each year. These injuries occur when there is damage or disruption to nerves that extend from the spinal cord and brain to the rest of the body outside of the central nervous system. They are often caused by trauma, compression, disease or inflammation.

When it comes to recovery of peripheral nerve lacerations, a patient typically has a 50% chance of limited or no return to normal function with conventional microsuture surgery.

“Even in the best-case scenarios, nerve injuries often don’t do well,” Dr. Isaacs said. “Despite our best efforts, we only have positive results half of the time, and this is after decades and decades of research in trying to understand how nerves heal.”

Subpar outcomes are due to a multitude of reasons.

First, time. Nerves take a long time to heal at about a millimeter per day or an inch per month.

Second, the type of cut. The cleaner and more direct the cut, the better the repair. But a clean cut, like with avocado hand, is the rare, “ideal” scenario.

Third, the location of the injury. The farther the injury is from the site of the movement, the longer the healing process will take. In the case of muscles in the hand, a nerve injury at the wrist does better than one near the shoulder. The nerves at the wrist are closer to the hand and require less distance for the signal to travel from the injured location.

Finally, the surgery itself is complicated and challenging. Microsutures, the current gold standard of care, are thinner than human hair. They require steady hands to place precise stitches and properly aligned nerve ends, and a small number of surgeons have the specialized training necessary to perform such surgeries.

With Nerve Tape, it’s just quicker, easier and gives me more satisfaction.

Geetanjali Bendale, Ph.D., research scientist, VCU Department of Orthopaedic Surgery

Properly aligned nerves are essential. Suturing nerves with too much of a gap allows for tissue growth between nerve stumps. Suturing too tight can result in nerves growing over each other. Both cause misalignment.

INVENTING A FASTER, BETTER STANDARD

In March 2023, Dr. Isaacs conducted a usability study of Nerve Tape at Massachusetts General Hospital in collaboration with Harvard Medical School in Boston. The study included some of the top microsurgeons in the country and six trainees ranging from mid-year orthopaedic residents to hand surgery fellows.

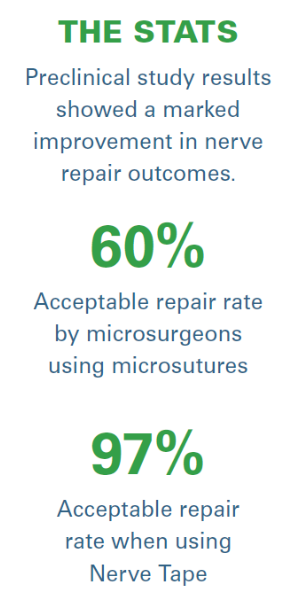

The group was tasked with completing a series of nerve repairs with microsutures that mimicked clinical scenarios while Dr. Isaacs and his team blind-judged the repairs based on alignment and time. For both groups of participants, the judges found that many of the microsuture repairs were suboptimally aligned, meaning that many of the nerve fascicles were overlapping or pointing in the wrong direction. This observation tracked with current data on outcomes. The microsurgeons had 60% acceptable suture repairs and trainees had 30% acceptable suture repairs.

The group then completed repairs using Nerve Tape for the first time. For both the advanced surgeons and the trainees, 97% of all repairs were deemed technically well aligned and acceptable. Timewise, the microsuture repairs took up to 15 to 20 minutes while Nerve Tape typically took about one to two minutes to apply. In the final phase of testing, the Nerve Tape proved to be two to three times stronger in repair. The study was submitted for publication and will be presented at the American Association for Hand Surgery meeting in January, where it has already been selected as the “Best Scientific Abstract.”

The group then completed repairs using Nerve Tape for the first time. For both the advanced surgeons and the trainees, 97% of all repairs were deemed technically well aligned and acceptable. Timewise, the microsuture repairs took up to 15 to 20 minutes while Nerve Tape typically took about one to two minutes to apply. In the final phase of testing, the Nerve Tape proved to be two to three times stronger in repair. The study was submitted for publication and will be presented at the American Association for Hand Surgery meeting in January, where it has already been selected as the “Best Scientific Abstract.”

“It’s very promising data and this was the kind of study that gets us most excited that we are headed for success,” said Dr. Isaacs, whose team worked through VCU Innovation Gateway to initially license the hooks to a company that specializes in making microneedles on metal discs that could be implanted into the muscle.

Nerve Tape’s success is based on the microhooks made of nitinol, an alloy of nickel and titanium, which is super elastic — nitinol is flexible and prevents metal crimping that could affect or compress the underlying nerve tissue when used in Nerve Tape.

The nitinol hooks are attached to a biological backing that minimizes tissue adhesions, protects the repair site and prevents misalignment of nerve ends. During the procedure, the nerve stumps are placed on the microhooks that engage the outermost layer of a peripheral nerve. The tape is then wrapped around the nerve ends to allow for additional microhook engagement as it creates a secure tube that acts as a guide for nerve fibers to grow in the correct direction and in proper alignment.

Geetanjali Bendale, Ph.D., joined Dr. Isaacs’ team at the time that Nerve Tape’s ultimate design was being finalized. As a research scientist and the main surgeon for Nerve Tape, she sets up experiments; analyzes data, histology and pathology; and writes papers to present.

Dr. Bendale said the most important element of nerve repairs is that the nerve ends should be well aligned, and any tension be distributed along the length of the repair. While the microhooks seemed to do this, it was also critical that the microhooks did not damage the underlying nerve fibers. She has completed countless suture repairs in the lab, and three out of 10 times is unhappy with the results despite having so much practice.

“With Nerve Tape, it’s just quicker, easier and gives me more satisfaction,” Dr. Bendale said. “I now think of repair success in terms of surgeon satisfaction. Surgeons who end up using Nerve Tape will hopefully have greater satisfaction in their repair.”

WHAT’S NEXT?

Nerve Tape is just a few months shy of being available on the market and accessible to surgeons for clinical use. A soft launch is planned for early 2024 to include the Mayo Clinic and about 10 major academic medical centers around the U.S.

Once implemented, the hope is that Nerve Tape will be considered a tool that will not only allow for better results on nerve repairs, but also speed up surgeries, which will open operating room capacities for other surgeries. Because of its ease of use, non-nerve specialists will be able to repair nerves without transferring to specialized centers. This will be particularly helpful in rural areas where there are no trauma hospitals nearby and could have potential future uses in military trauma care.

The research team has a grant from the Department of Defense for an ongoing research project to modify Nerve Tape to facilitate other treatments that might improve nerve regeneration. Additional research will continue to define repair parameters and determine different ways to apply Nerve Tape.

“People have talked about it before, but nobody has ever made something similar to the prototypes we have,” Dr. Isaacs said. “Once we started thinking about it, we realized that there are many different ways to use microhook technology inside the human body to fix all sorts of injuries and improve patient recovery.”

The myriad possibilities for Nerve Tape’s application beyond nerve repairs are a sure sign this invention will be sticking around for a long time. Dr. Isaacs is confident that Nerve Tape can be used for a host of other nerve surgeries beyond the extremities such as maxillofacial surgeries and breast reconstruction surgeries for patients recovering from breast cancer.

“Nerves are my passion and will continue to be,” Dr. Isaacs said. “And if this is as successful as I believe it will be, then this will certainly be impactful to patients around the world and VCU’s national reputation.”

If you would like to support this research, please contact Andrew Hartley, director of development with VCU’s Office of Medical Philanthropy and Alumni Relations, at 804-628-5312 or aphartle@vcu.edu.

Discover More

Read more features like this in the winter issue of NEXT magazine.