Exploring VCU Health’s Leadership in Sickle Cell Care and Research

Editor’s Note: This is an excerpt of a feature that appeared in the summer 2021 issue of NEXT magazine. Our online edition has the full article and more great stories about innovative research happening on the MCV Campus.

***

The trouble usually starts around six months after birth. By that point, children born with sickle cell disease stop producing fetal hemoglobin, and the first symptoms begin.

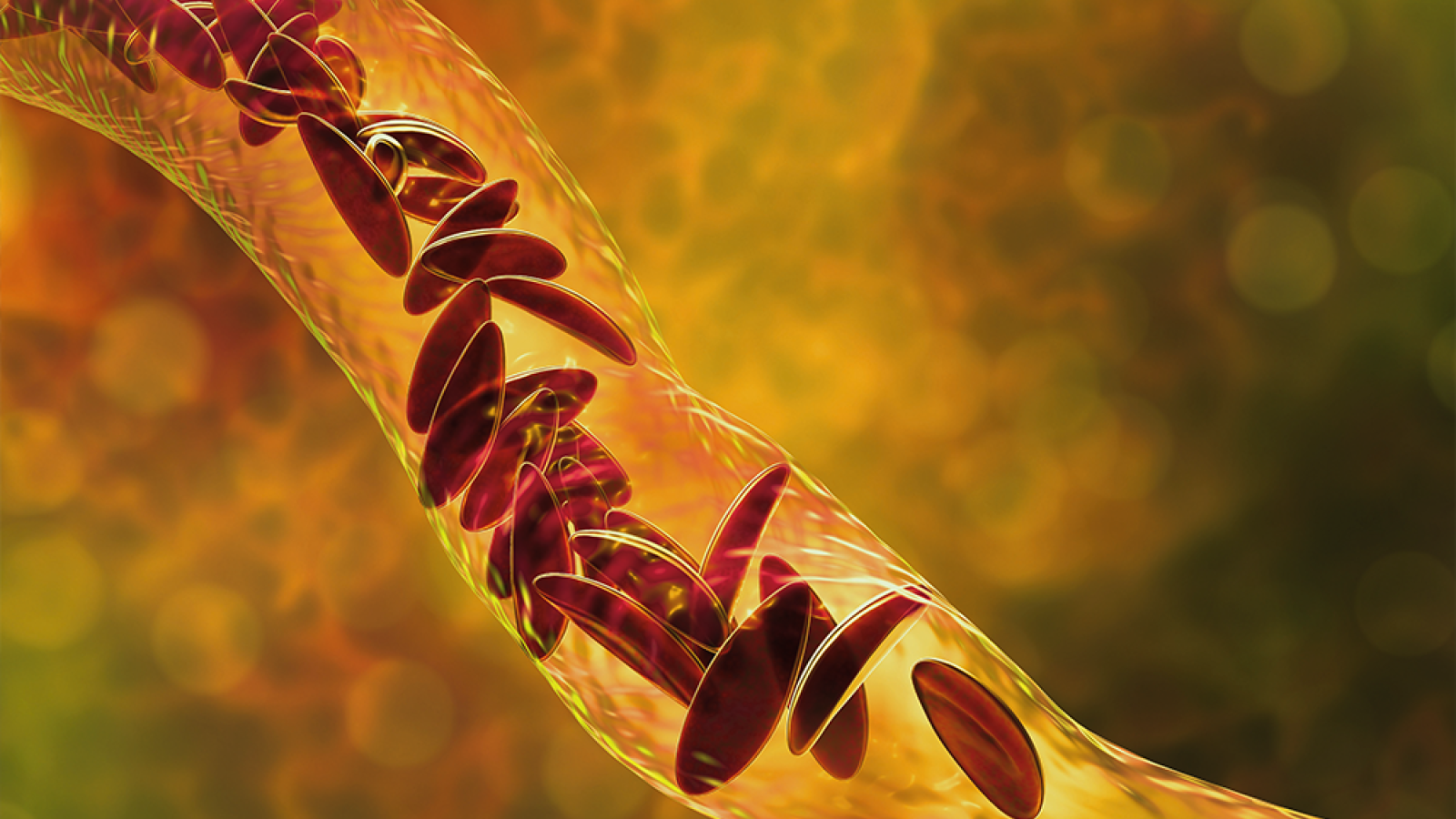

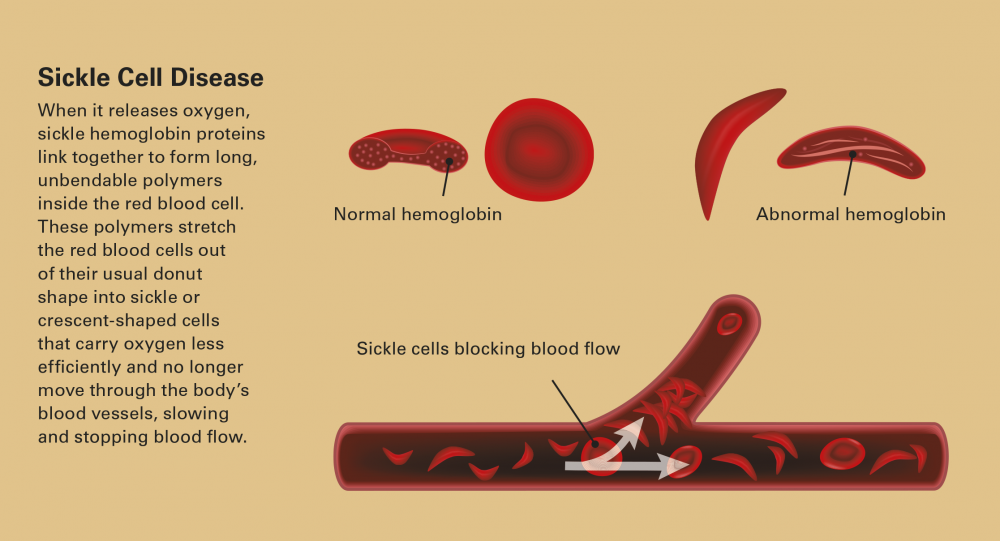

In sickle cell disease, a genetic variation results abnormal hemoglobin which cannot carry oxygen as well as regular hemoglobin. These sickle or crescent-shaped cells no longer move through the body’s blood vessels, slowing and stopping blood flow.

Chaos ensues all over the body. Organs no longer receive oxygen. Pain begins, and sickled red blood cells break open and die, spilling poisonous waste into the body. This vicious cycle continues. Less oxygen means more hemoglobin polymers, and in turn more clogged blood vessels, more red blood cell death, more pain and more anemia. Eventually, massive tissue and organ damage and a weakened immune system shorten the lifespan of many patients who experience painful crises that become chronic, with frequent emergency room visits, failing organs and a sense of helplessness.

For too many years, the medical community and society abandoned these patients who, in the U.S., are predominately Black. Many doctors threw up their hands and told children and parents not to worry about making life plans or attending school, since they likely would not live long past their 20th birthday. Those lucky enough to survive were told there was little to do for them other than to give them opioids. Most researchers overlooked the disease. Almost all of society stigmatized patients with the condition.

On the MCV Campus, however, a strong five-decade-long history of outreach and research has made VCU Health a leader that helps these forgotten patients. It started in 1972, when Congress passed the National Sickle Cell Disease Control Act. The law provided the first-ever authority to set up education, screening, research and treatment programs for SCD. VCU started one of the first efforts to screen all newborns in Virginia for sickle cell disease.

“VCU was in the unique position of being one of the first 19 institutions to have a sickle cell disease outreach program,” said Wally Smith, M.D., professor and scientific director of the VCU Center on Health Disparities and director of the VCU Health Adult Sickle Cell Program. “Florence Neal Cooper Smith and Dr. Robert Scott started the clinic in the face of overwhelming opposition. They were swimming upstream the whole time. Now people look to us as authorities in this area. We are clearly one of the top 10 centers in the country — whether you measure by number of patients, funding from the federal government or industry, or research productivity.”

Dr. Smith directs VCU’s Adult Sickle Cell Medical Program, which now cares for nearly 700 patients, three times as many as when he arrived on the MCV Campus in 1991. VCU Health currently serves SCD patients from across Virginia, intentionally reaching and educating patients and providers as far away as the Eastern Shore. The resulting adult population growth underscores the need for new investment in research and patient care for this expanding patient population. That’s the professional challenge and calling that Dr. Smith has been pursuing since 1984. He has been advising efforts to develop new treatments, trying to better understand and remove barriers to care, and advocating with policymakers at the local, state and national level to achieve equity in funding and equitable lifespans for adults with SCD.

“I saw orphans needing a home,” Dr. Smith said. “There’s a whole generation of Americans who don’t remember the days when sickle cell patients were not living to adulthood. They don’t understand how much we have had to go through to get care to where it is today.”

RESEARCH AND TREATMENT DEVELOPMENT

In addition to his clinical duties, Dr. Smith consults on a drug development project based at the VCU School of Pharmacy. He’s working with Martin K. Safo, Ph.D., professor in the school’s Department of Medicinal Chemistry, to develop compounds that help improve the oxygen-carrying capacity of red blood cells in sickle cell patients and destabilize the polymers from causing further sickling, which in turn instigates the pain and other chronic and potentially life-threatening issues.

“This is a team effort,” said Dr. Safo, who is affiliated with the school’s Institute for Structural Biology, Drug Discovery and Development. “We have spearheaded global efforts over the past four years to develop new compounds to treat sickle cell disease with partners like Dr. Osheiza Abdulmalik at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and King Abdulaziz University in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.”

Dr. Safo has been working on drug discovery for sickle cell for almost 30 years. Originally from Ghana, he knows firsthand how the disease can affect people. Two of his cousins were born with sickle cell, and one has already died from the disease.

Dr. Safo’s research found promise in the byproduct of a sugar molecule named 5-HMF. He and his team took the research far enough to license the compound to a pharmaceutical company to produce for clinical trials. That company, unfortunately, went bankrupt and future studies stalled, but Dr. Safo and his team had managed to change the paradigm on exploring potential therapies.

The VCU Health team continues to explore and improve potential treatments. Their latest promising work is a compound named VZHE-039, a novel anti-sickling agent that the team hopes to advance for clinical trials in the next year. Unlike therapies currently on the market, this new compound designed on the MCV Campus works on two levels: first, it increases the concentration of the non-polymerizing sickle hemoglobin; second and uniquely, it directly destabilizes the sickle hemoglobin from forming polymers, thus preventing further sickling and reducing the risk of pain and organ damage downstream. The candidate is rapidly advancing toward Phase I/II clinical trials.

“Our compound is rather unique,” Dr. Safo said, “The dual anti-sickling activities of VZHE-039 would be critical to successfully ameliorate the disease phenotype in areas of severe hypoxia.”

This spring, the team received funding from the National Institutes of Health to continue the effort to develop this new treatment. One thing has changed, however. After their earlier experiences with licensing to a company stalled progress, the researchers formed their own company, IllExcor Therapeutics, to develop the compounds coming from research being conducted at VCU for the treatment of SCD. The name is a combination of the word “ill” and a shortening of the word exorcism, a clarion statement of the company’s purpose.

“We have a lot of hope that these therapies will be a huge benefit,” Dr. Smith said of the team’s efforts. “And that this compound can be added to the arsenal of potential tools. It’s very encouraging. I would say that the future is bright right now. Our biggest challenge remains awareness.”

If you would like to support sickle cell disease research and care on the MCV Campus, please consider making a gift to the Florence Neal Cooper Smith Professorship by contacting Brian Thomas, MCV Foundation vice president and chief development officer.